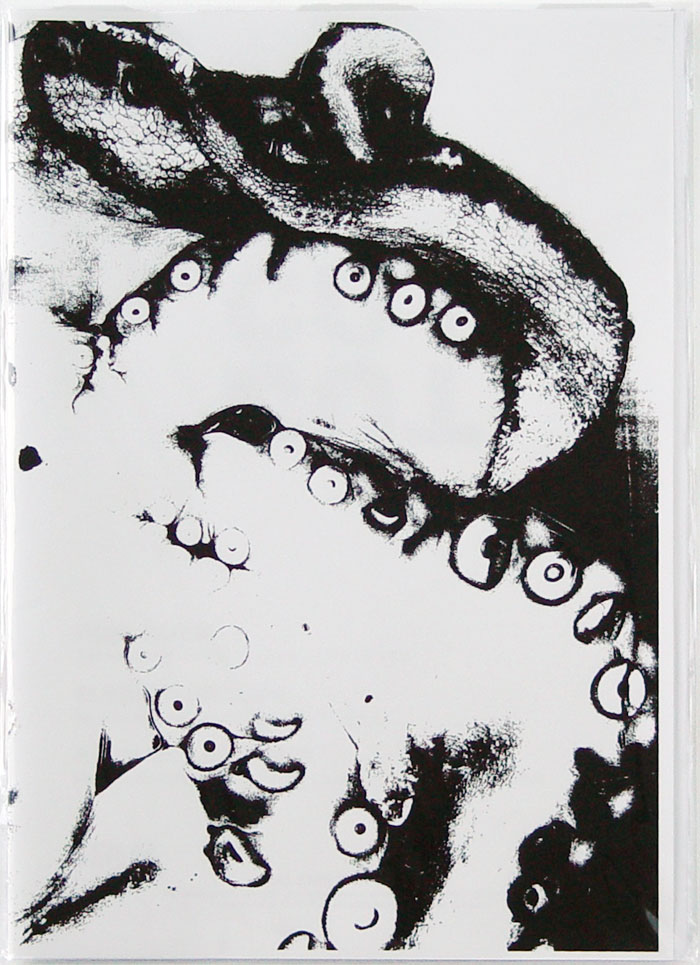

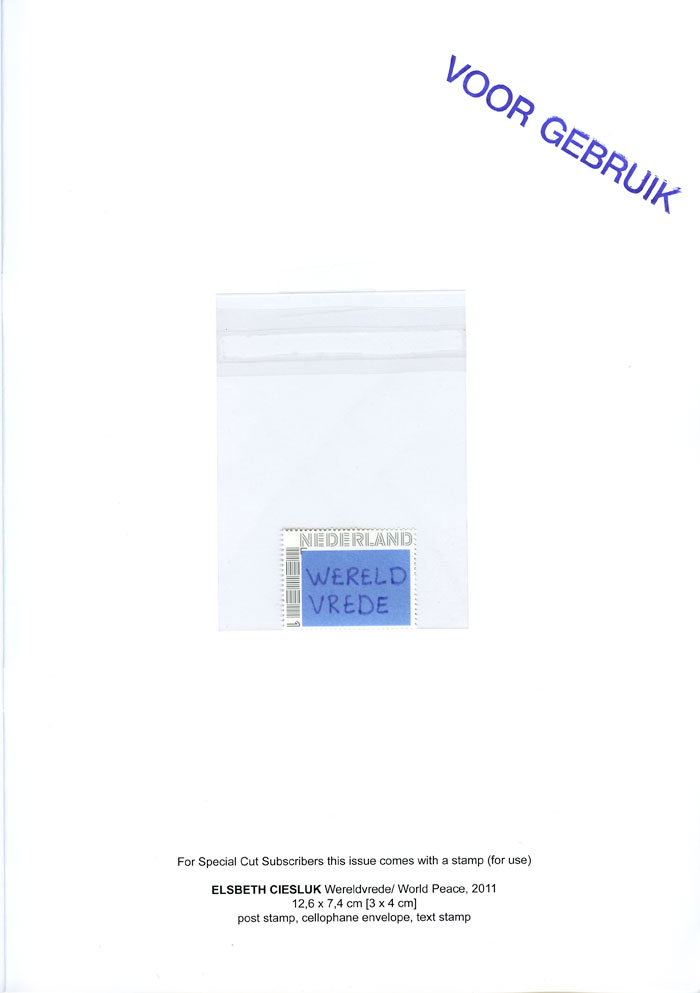

CUT magazine about artissue 13 - 2014ROEL HIJINK Zelf een kamp bouwen / Building a camp yourself ELSBETH CIESLUK Wereldvrede (voor gebruik) / World Peace (for use) RAPHAEL LANGMAIR How to catch an octopus; One represented by the smell of another Editorial board: Kees van Gelder Iris van Gelder

Zelf een kamp bouwen ROEL HIJINK Tien jaar geleden sloeg mij de schrik om het hart. Mijn zoon, toen een jaar of acht, speelde met Lego en had daarmee een bouwwerk gemaakt. Nieuwsgierig vroeg ik wat het voorstelde. “Een gaskamer” was het antwoord. Een gaskamer mompelde ik hem zachtjes na. Een gaskamer. Wat was er gebeurd, was hij besmet geraakt met het kwaad waaraan hij tijdens onze vakanties was blootgesteld, toen het mij goed uitkwam een vakantiedag op te offeren ten behoeve van onderzoek en wetenschap? Had de opvoedkundige taak gefaald? Had ik hem überhaupt mee moeten nemen naar een voormalig kamp? Een bezorgde professor had me nog zo gewaarschuwd. Als kind had hij gruwelijke foto’s uit de oorlog gezien waarvan de beelden nog lang in zijn hoofd rondspookten. Inderdaad, gruwelijke foto’s waren er in het kamp genoeg te zien geweest maar die had ik mijn zoon onthouden. Alleen het voormalige kampterrein hadden we bezocht met daarop de architectonische resten van wat er van het kamp over was. De toegangspoort was nog wel intact en hier en daar stond nog een barak. De rest was leegte. Het was moeilijk geweest uit te leggen wat nu de functie van een concentratiekamp was. Een gevangenis uitleggen is niet zo moeilijk, daar worden misdadigers opgesloten, mensen die hadden geroofd of gemoord. Maar hoe leg je een concentratiekamp uit, waarvan de bedenkers nu als perverse, rationalistische bureaucratische technocraten van de dood worden gezien en waar onschuldige mensen worden opgesloten. De omgedraaide wereld. En in deze gevangenis werden mensen ook nog eens vermoord, door middel van een gaskamer. Tja, hoe moet dat in een kinderziel zijn aangekomen. En nu had hij een gaskamer van Lego gebouwd en ik had gewenst dat ik hem nooit daarheen had meegenomen. Toen ik vroeg hoe de gaskamer werkte antwoordde hij rustig “Hier gaan de boeven in en daar komen ze er weer uit als goede mensen.” Door mijn strak gespannen lippen ontsnapte een straaltje samengeperste lucht en mijn lichaam ontspande. Toen ik hem nog niet zo lang geleden vroeg of hij zich kon herinneren dat hij als kind een gaskamer van Lego had gebouwd kon hij dat niet. Toch was ik niet gerust. Hij zei dat het zeker tien jaar geleden was dat hij met Lego speelde dus hoe moet hij dat nog weten. Maar ik moet nog vaak horen dat we op vakanties nooit naar pretparken gingen en alleen maar oorlogsmonumenten bezochten. Dat is niet helemaal waar, maar als dat zo herinnerd wordt dan is dat wel waar, althans voor die persoon. En zo weet ik zeker dat hij een gaskamer van Lego heeft gebouwd, een goede gaskamer. Dat wel. De herinnering aan de Lego-gaskamer spookt vaak door mijn hoofd maar kwam expliciet boven drijven ten tijde rond de commotie over het zogenaamde Buchenwaldhek. Tijdens de televisie-uitzending De Wereld Draait Door begin december 2011 mochten Job Smeets en Nynke Tynagel, samen zijn ze designbureau Studio Job, een toelichting geven op hun werk in het Groninger Museum. Al snel ging het echter over een ontwerp van een hek rond het landhuis van een verzamelaar. De fundamenten voor de poort waren al gestort. Op de bouwtekening die getoond werd was te zien dat het hekwerk was gemaakt van prikkeldraad dat vakkundig vormgegeven was. De poort bestond uit twee schoorstenen verbonden met een boog van wolken. Op het hoogste punt van de boog hing een bel. Deze bel was voorzien van de Latijnse tekst suum cuique, in het Nederlands ‘Ieder het zijne’. Vertaald in het Duits werd dat ‘Jedem das Seine’. Dat hadden ze beter niet kunnen doen. De associatie met kamp Buchenwald was snel gelegd. Hier immers prijkte deze spreuk in de toegangspoort. Het prikkeldraad en de schoorsteenpijpen met wolk werden geassocieerd met de vernietigingskampen. De verwijzing naar Buchenwald was door Studio Job niet zo bedoeld althans op de vraag of het hek niet heel veel te maken heeft met de concentratiekampen in Duitsland reageerde Smeets: “Oehhh, zo zou ik het niet per se willen zeggen”. De tekst ‘Ieder het zijne’ is eigenlijk een hele luchtige uitspraak aldus Nynagel en de boog met klok was meer een verwijzing naar de poort in de film Once Upone A Time In The West volgens Smeets. Waarom het duo de associatie met Buchenwald en de vernietigingskampen wilde afzwakken was niet duidelijk en al helemaal niet nadat een tafelkleedje werd getoond voorzien van een design dat in abstractie Auschwitz-Birkenau verbeeldde. Het ontwerp was bedoeld als tafelkleedje voor in de VIP lounge, een functionele ruimte die het duo had ontworpen voor het Groninger Museum. In een toelichting op internet laat Job Smeets weten dat het hekwerk een verwijzing is naar “Guantanamo Bay, de Jappen kampen, de kampen in Bosnië en natuurlijk de tweede wereldoorlog.” Het tafelkleedje met Auschwitz-design was een reactie op het kunstwerk Hell van Jake en Dinos Chapman dat in 2002-2003 in het Groninger Museum te zien was geweest. Omdat zij in hun werk altijd op zoek zijn naar iconen zochten ze ook naar het icoon van een hekwerk met de niet oninteressante vraag “wat is een hekwerk en waarom hebben wij als mensen een hekwerk nodig?” Zo kwamen ze tot het hierboven beschreven kunstwerk. Doel van deze Holocaustkunst was een discussie uit te lokken over de positie van design ten opzichte van kunst. Welke discussie bleef verder onduidelijk ook in de tweede uitzending een dag later. Een media rel was geboren. Deskundigen kwamen aan het woord en spraken schande, omwonenden en het Centrum Informatie en Documentatie Israël (CIDI) hadden een bouwstop geëist, omdat het ontwerp choqueerde en geen respect had voor de slachtoffers. De bouw van het hek ging definitief niet door toen journalist Arnold Karskens in het Centraal Archief Bijzondere Rechtspleging had ontdekt dat de grootvader van Jack Bakker (de verzamelaar en opdrachtgever voor het hek) Jacobus Hendrikus Bakker lid was van de NSB en tussen 1940 en 1945 werkzaamheden had verricht voor de Duitse Luftwaffe en de Duitse overheidsbouworganisatie Todt. Na de oorlog zat J.B. Bakker anderhalf jaar vast wegens collaboratie. Voor Jack Bakker was deze onthulling van zijn opa de druppel. ‘“Zeer tot mijn spijt heb ik moeten constateren dat het wordt geassocieerd met zaken die ik niet heb gewenst toen ik de opdracht gaf tot het maken van de poort”, zegt Bakker.’ Het Buchenwaldhek dat inmiddels nazi-hek was gaan heten ging roemloos ten onder. Misschien best wel jammer, want de vragen over wat een hekwerk is en waarom wij zo'n systeem nodig hebben werden zo niet nader in beeld gebracht. Wat had Studio Job nu verkeerd gedaan? Kunst over de Holocaust, of Holocaustkunst, is inmiddels een eigen genre geworden waarbinnen choquerende kunstwerken niet geschuwd worden. De Britten Jake en Dinos Chapman hadden in 2002-2003 in het Groninger Museum Hell geëxposeerd. Een kunstwerk bestaande uit een aantal vitrines waarin het Duitse concentratiekamp was nagebootst met middelen uit de modelbouw. Een aantal jaren eerder had de Poolse kunstenaar Zbigniew Libera LEGO Concentrationcamp Set (1996) ‘op de markt’ gebracht. Een set van Lego dozen waarmee een concentratiekamp gebouwd kon worden. Of er ook een gaskamer gebouwd kon worden, weet ik niet. En om bij de mode en design van Studio Job te blijven, in 1998 had de Amerikaan Tom Sachs Prada Deathcamp ontworpen, een maquette van een kamp gemaakt uit een verpakkingsdoos van het Italiaans modemerk. Ook deze kunstwerken hadden de nodige opschudding veroorzaakt maar ze werden wel geëxposeerd en zelfs aangekocht door musea. Het probleem van Studio Job was dat een goed verhaal achterwege bleef. Of zoals kunstcriticus Rutger Pontzen het schrijft: “Ondanks het fingerspitzengefuhl dat Smeets en Tynagel voor ‘onze tijd’ hebben, kun je het ontwerpduo niet op enig engagement betrappen. Hun hedonistische benadering maakt van alles wat ze onder handen krijgen een blingblingwereld: kasten, wereldbollen, theekopjes, glas-in-loodramen. En om het oeuvre een beetje prikkelender temaken, nu ook een concentratiekamphek. De Holocaust als design, het zou natuurlijk de volgende stap in de acceptatie van de oorlog kunnen zijn. Maar dat is het ‘m juist: wie wil nu dat de jodenvervolging een geaccepteerd lifestyle-ding wordt”. Dat een inhoudelijke discussie over de ontwerpen van Studio Job uitbleef was jammer want wat ze wel goed hadden gezien en wat het tafelkleedje, hoe misplaats misschien ook, wel goed verbeeldde, was het feit dat Auschwitz een icoon was geworden. Wat dat icoon inhield of hoe, waarom en waarvan Auschwitz een icoon was geworden werd helaas niet duidelijk. Ook is niet duidelijk geworden wat de betekenis is van het Buchenwaldhek, behalve een icoon van het fenomeen hek. Wat gebeurt er nu precies als je zelf een kamp nabouwt of in dit geval een gedeelte ervan? Met deze vragen kwam de herinnering van de Lego-gaskamer weer boven. Mijn zoon had toen hij zijn gaskamer bouwde de intentie om het kwade in de mens te transformeren in het goede, een zekere mate van engagement kan hem niet ontzegd worden. Ook Libera had zo zijn bedoelingen met zijn LEGO Concentrationcamp Set die gezocht moeten worden, eenvoudig gezegd, in het aan de kaak stellen van traditionele dogma’s omtrent de herinnering aan de Holocaust, het onderricht en de positie van hedendaagse kunst. Maar wat beoogde Studio Job nu met het Buchenwaldhek of misschien interessanter, wat bezielde de verzamelaar om de toegang tot zijn landgoed te voorzien van een poort die de associatie opriep met de vernietigingskampen? Zelf een kamp bouwen, kunstenaar Joep van Lieshout had het ook al eens gedaan. Niet met de bedoeling om de herinnering aan de Holocaust en de educatie daarover door middel van kunst aan de kaak te stellen maar om een samenleving te creëren, Slave City, die de maximale winst oplevert ten bate van een hoge welvaart. Alle voorwerpen worden gerecycled, zelfs de slaven als deze niet meer functioneren. Zijn gebruik van slaven doet denken aan Animal Farm van George Orwell. Het paard met de naam Klaver wordt als hij doodziek is niet naar een ziekenhuis gebracht, maar verkocht aan de vilder Adolf Slijmpot, Paardenslager en Lijmkoker. Handelaar in Huiden en Beendermeel. Leverancier aan Hondenkennels. Van de opbrengst werd jenever gekocht. Slave City is een model voor een utopische samenleving waar alles zeer rationeel is geregeld, voor bestuurders utopisch voor de bewoners een anti-utopie. Ook de Duitse concentratiekampen waren rationeel van opzet en qua structuur moest het de ideale stad/samenleving vormen. De architectuur stond in dienst van toezicht en discipline van haar bewoners en zo nodig vernietiging. Deze rationele samenleving waar alles precies liep als een goed lopend uurwerk had Frank Zappa geïnspireerd tot zijn film 200 Motels. In deze film liet hij het Royal Philharmonic Orchestra optreden in een nagebouwd concentratiekamp. Het kamp diende als symbool voor alles wat de individuele vrijheid beknot en speciaal de creatieve vrijheid. Het concentratiekamp in de film 200 Motels is voor Zappa een vermaakconcentratiekamp, een muziekkamp gesponsord door de United States Goverment. Boven de entree van het kamp in 200 Motels stond ‘Work liberates us all’, een cynische verwijzing naar de nazi-kampen met haar ‘Arbeit macht frei’ poorten. Met de verwijzing naar de concentratiekampen gaf Zappa zijn visie op het muzikantenbestaan. De muziekindustrie is corrupt en onderhevig aan het kapitalistische systeem dat de creativiteit inperkt ten gunste van de business. Wat Zappa ons wilde laten zien is dat het leven in de schijnbaar vrije stad weinig verschilt van de organisatievorm in een concentratiekamp en dat de machtsverhoudingen binnen deze systemen ook te vinden zijn binnen het zogenaamde vrije muzikantenbestaan, het spelen in een band en het leven on the Road. Het Royal Philharmonic Orchestra musicerend in het nagebouwde concentratiekamp was een metafoor van het muzikantenbestaan. “Je zou kunnen denken dat Slave City allerlei overeenkomsten vertoont met onze eigen samenleving. Maar ik zal nooit zeggen: ‘dit is goed of dit is slecht’. Dat zoekt de toeschouwer zelf maar uit.” Aldus Joep van Lieshout. De kampen van Van Lieshout en Zappa zijn indirect verwijzingen naar organisatievormen en systemen in ons dagelijks leven. Er kwam weer een herinnering bij mij boven. De rituelen die ik meemaakte bij het muziekfestival Lowlands, deed me in analogie deed denken aan die in een kamp zoals ik in dagboeken van overlevenden had gelezen. Het op naam gekochte kaartje werd bij de toegangspoort omgezet in een barcode, de pols werd voorzien van een bandje, persoonlijke eigendommen in de vorm van drugs en drank moesten worden achtergelaten in afvalcontainers: gegeten en gedronken mocht alleen dat wat door de organisatie werd verkocht. Voor de aanschaf had de organisatie eigen ‘kampgeld’ in roulatie gebracht. Slapen gebeurde op overvolle kampeerterreinen, die nachts continue werden bewaakt door felle schijnwerpers en een ordedienst met honden. Voor alles: toegang, eten, drinken, sanitair, tent met muziek moest in lange rijen worden gewacht. Zonder opgaaf van reden kon je zo maar aangehouden worden en gefouilleerd. Het idee dat iedereen zich zelf mag of moest zijn binnen de hekken van het festival was paradoxaal. Of anders gezegd, iedereen was gemortificeerd tot een universele festivalganger die zich schikte naar de wetten van de organisator. De organisatiestructuur van dit festival deed niet veel onder aan die we kennen van de totale architectuur: gekenmerkt door een barrière van gesloten deuren, hoge muren, prikkeldraad of natuurlijke scheidingen als rotswanden, water, bossen of heidevelden. Alle aspecten van het leven als slapen, werken en vermaken voltrekken zich op dezelfde plaats en onder het zelfde gezag. Deze activiteiten zijn geordend in een strak schema. Bedoeling is dat de bewoners gedwongen worden te veranderen wat al begint bij binnenkomst: de mortificatie, waar het ego wordt doodgemaakt. Hij moet zijn persoonlijke bezittingen afgeven, zijn haar wordt geschoren, krijgt een uniform aan en zijn naam wordt veranderd in een nummer. Het is een ritueel dat we zien in kazernes, gevangenissen, kloosters en internaten en concentratiekampen. Ik ben nooit meer naar dat festival geweest. En zal er waarschijnlijk ook nooit meer komen toen ik las dat er proeven zijn genomen met polsbandjes voorzien van een gps-systeem. Iedere bezoeker kan gevolgd worden en ongewenst gedrag kan zo worden herkend en uitgebannen. Woodstock en Kralingen zijn ineens heel ver weg. PVV- politica Fleur Agema ontwierp aan de Hogeschool van de Kunsten Utrecht (2004) een voor haar ideale gevangenis. Kunstenaar Jonas Staal had haar ontwerp, beschreven in een 344 pagina’s tellende masterscriptie, vertaald naar een maquette. De gevangenis bestaat uit een massief gebouw en is groots, donker en dreigend. Het gebouw is gemaakt van zwart en grijs beton en omringd door torenhoge hekken. De cellen zijn betonnen holen met een betonnen verhoging als bed en een betonnen uitstulping met een gat als wc. Een spleet in de muur dient als raam. Het geeft een streepje licht. De gevangenis heeft ook een afdeling waarin de gevangenen worden voorbereid op een terugkeer in de samenleving. De afdelingen hebben namen als: ‘Het Fort’, ‘De Legerplaats’, ‘Artillerie Inrichting’ en ook ‘De Wijk’. De Wijk is een imitatie-vinexwijk met camerabewaking. Staal kwam tot de conclusie dat Agema’s architectuur naadloos past binnen het samenlevingsmodel dat de PVV voorstaat: “[…] het streven naar een samenleving gericht op discipline, efficiency en productiviteit, waarin alle ‘onproductieve elementen’ worden weggezuiverd”. Staal: “Hier zijn het gevangenen, maar het zijn in de PVV-ideologie net zo makkelijk moslims, werklozen of kunstenaars. Iedereen die niet past in hun productiviteitsmodel wordt uitgesloten.” Het doet denken aan Slave City van Van Lieshout. Om toezicht te houden op mensen en ze te disciplineren is vandaag de dag geen steen, ijzer en hout meer nodig. De digitalisering rukt op. Zo kunnen bijvoorbeeld vrijheidsstraffen met zogenaamde elektronische detentie buiten de inrichting uitgezeten worden. Muren, prikkeldraadomheiningen, wachttorens, grachten, toegangspoorten – alle bekende iconen van totale architectuur zoals te vinden bij het concentratiekamp – kunnen worden vervangen door elektronische systemen. Je zou kunnen spreken van digitale muren bestaand uit een netwerk van videocamera’s, digitale passen, iris-scanners en gezichtherkenningsystemen. Systemen die niet alleen toegang geven tot een bepaald gebied, maar ook leefgebieden moeten beschermen tegen kwaadwillenden. Londen en ook Amsterdam beschikken over een ring of steel (de oude slotgracht) van honderdduizenden videocamera’s op de rondweg die de stad veilig moeten maken. Systemen die steeds geavanceerder worden. Zo is een wetenschappelijk onderzoek gaande naar bewakingssystemen die abnormaal gedrag herkennen. Zo zou een intelligente surveillancecamera de privacy beter kunnen beschermen. De computer herkent menselijke torso’s, armen en benen op zo’n manier dat beter is te bepalen met welke bedoelingen personen bewegen. Ook overheidscontrole via digitale sociale netwerken is nog maar een kwestie van tijd. We weten dat deze ontwikkeling gaande is, maar in dienst van onze veiligheid nemen we daar geen aanstoot aan of we zijn er nog steeds onverschillig voor. Er is een theorie dat middeleeuwse dorpen zijn uitgevonden om de boeren onder controle te houden en ze harder te laten werken. En dat het kasteel er niet was voor de bescherming, maar dat het de wachttorens waren van deze concentratiekampen. Wanneer zijn onze steden zulke concentratiekampen met de camera’s als digitale wachttorens? Wat als Studio Job een poort had ontworpen die minder expliciet naar Buchenwald en Auschwitz had verwezen. Deze namen en plekken zijn verbonden met traumatische ervaringen en pijnlijke herinneringen. Dat het ontwerp als schokkend werd ervaren is niet verwonderlijk. De wond van Auschwitz is nog lang niet genezen. Sterker, de Jodenvervolging is een moreel ijkpunt geworden in de geschiedenis die steeds weer opnieuw ontdekt wordt en actueel blijft, wel of niet via incidenten als het Buchenwaldhek. Maar wat als het duo een poort had ontworpen die meer de vraag zichtbaar maakte wat een hekwerk is en waarom wij hekwerken nodig hebben? Dus een poort dat het systeem en structuur van het kamp als thema had. En deze poort, of poorten hadden geplaatst boven de toegangswegen naar Amsterdam om ons erop te attenderen dat we een toezichthoudende leefomgeving naderen. Een leefomgeving gecreëerd voor onze eigen vrijheid en veiligheid maar ook zo nodig voor het tegendeel gebruikt kan worden, om ons, denkend aan het middeleeuwse dorp en het ontwerp van Fleur Agema, te disciplineren tot efficiënte boeren en burgers. Een poort die een discussie kon uitlokken van wat de gevolgen kunnen zijn van het creëren van leefomgevingen met toezichthoudende digitalisering. En wat was gebeurd als het Buchenwaldhek wel was gerealiseerd rond het landgoed van de verzamelaar? Er was een bel opgehangen zonder de aanstootgevende spreuk en de poort met hekwerk was even grimmig als dat we van de kampen gewend zijn, wat had hij dan laten bouwen en met welke bedoelingen? Had hij zijn eigen kamp gebouwd? Was hij een aanbidder en verzamelaar geworden van het nazi-erfgoed, hoe nep de poort ook zou zijn geweest? Of had hij ons een spiegel voorgehouden van de wijze waarop tegenwoordig ideale woongemeenschappen worden bedacht en gebouwd. Wie dat wil zien moet eens een wandelingetje maken door een welgestelde buitenwijk. De villa’s zijn omgeven door hoge muren of hekwerken voorzien van talloze camera’s. In de serie Nederland van boven was een nieuwe trend te zien. Woonwijken beschermd door een gracht en afgesloten door poorten die niet onderdoen voor de oude kasteel- of stadspoort, ook wel aangeduid als gated communities. Maar toch. Volgens mij had de verzamelaar geen kwaad in zin toen hij Studio Job de opdracht gaf tot het ontwerpen van een hekwerk. Maar wat hij precies met het hekwerk wilde uitdrukken bleef onduidelijk. Zijn argumentatie om met het project te stoppen blijft cryptisch, “Zeer tot mijn spijt heb ik moeten constateren dat het wordt geassocieerd met zaken die ik niet heb gewenst toen ik de opdracht gaf tot het maken van de poort.” Maar wat had hij gewenst? Natuurlijk een hekwerk rond zijn bezit. En zijn bezit is behalve landgoed met huis een kunstverzameling. Hij wilde zijn verzameling veilig stellen en net als vele musea doen, een systeem creëren zodat de kunst voor nu en het nageslacht behouden blijft. Blijkbaar zit de samenleving zo in elkaar dat wel haast een soort van concentratiekamp gebouwd moet worden (dát had Studio Job ons willen laten zien natúúrlijk) om de kunst veilig te stellen. Welk museum is tegenwoordig niet voorzien van detectiepoortjes, toezichthoudende camera’s en bewakers (suppoosten genoemd) die de bezoeker zo nodig op de voet volgen tot hij weer buiten staat. Het museum als kamp, Van Lieshout had het kunnen verzinnen, maar wel een kamp ter verheffing van de burger want daartoe zijn musea tenslotte ooit eens opgericht. De verzamelaar had als het Buchenwaldhek was gerealiseerd een goed kamp gebouwd. Bezoekers hadden zijn kunst kunnen bewonderen tegen de tijd dat zijn landhuis een museum was geworden; zo als dat dan tegenwoordig gaat. Ze hadden rondgedwaald en verlicht zijn landgoed verlaten. Het had niet zo mogen zijn. De verzamelaar was nog voor de bouw getransformeerd tot een kwaadaardige kampcommandant. Roel Hijink studeerde aan de Academie voor Beeldende Kunsten Maastricht en Kunstgeschiedenis aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam. In 2010 promoveerde hij op het proefschrift 'Voormalige concentratiekampen. De monumentalisering van de Duitse kampen in Nederland', dat in 2012 bij Uitgeverij Verloren in boekvorm verscheen. Momenteel doet hij aan de Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam onderzoek naar de wijze waarop de herinnering aan de Duitse kampen in de beeldende kunst vorm heeft gekregen. voor noten zie hieronder English text Building a camp yourself ROEL HIJINK Ten years ago I was seized with alarm. My son, at that time about eight years old, played with Lego and had built an edifice out of it. Being curious I asked about what it represented. 'A gas chamber', he answered. A gas chamber I mumbled repeating him. A gas chamber. What has happened, was he infected by the evil he was exposed to during our holidays, during which it was quite convenient for me to sacrifice a holiday on behalf of research and science? Failed the pedagogic task? Should I have taken him to a former camp, anyway? A concerned professor did warn me as such. As a child he had seen gruesome photos from the war of which the haunting images ran through his head for a long time. Indeed, in the camp were enough horrifying photos to be looked at but I abstained these from my son. We only visited the former camp compound with architectural remains of what once used to be the concentration camp. The access gateway was still intact with here and there even a barrack. The rest was an empty place. It had been difficult to explain the function today of a concentration camp. To illustrate the function of a prison is not that difficult, here criminals are incarcerated, people who have robbed or murdered. But how do you explain a concentration camp of which the inventors are now seen as pervert, rationalistic bureaucratic technocrats of death and where innocent people are imprisoned. The world up side down. And above all here in this prison people were killed, by means of a gas chamber. Well, how will this have arrived in a children's soul. And now he has built a gas chamber of Lego and would have wished that I never took him there. When I asked him how the gas chamber would operate he quietly answered, "Here the rascals enter and there they come out again as good people." Between my tensed lips a small jet of pressed air came out and my body relaxed. Not so long time ago when I asked him if he could remember that as a child he had built a gas chamber of Lego he could not recall that. Yet I was not at ease. He said that it was certainly ten years ago that he played with Lego, so how should he still know. But still very often I have to listen patiently to stories that we never visited amusement parks during our holidays and only went to memorials of war. That is not completely true, but if that is remembered as such then that is true, at least for the person in charge. And in this sense I definitely know that he has built a gas chamber of Lego, that is to say a good gas chamber. The memory of the Lego gas chamber haunts often through my mind but popped up explicitly during the commotion of the so-called Buchenwald fence. During the television broadcast De Wereld Draait Door at the beginning of December 2011 Job Smeets and Nynke Tynagel, together forming the design office Studio Job, got the opportunity to make a statement about their work in the Groninger Museum. However very quickly the subject turned over to a fence all around the manorial estate of a collector. The foundations of the gate already had been embedded in concrete. A presented drawing showed that the fence was made of barbed wire competently designed. On the left and right side the gate was built up with two chimneys joined by an arch depicting clouds. On the highest point of the arch a bell hung. This bell was supplied with a Latin text suum cuique, meaning in English ‘To each his own'. Translated in German that is ‘Jedem das Seine’. This they could better not have done. An obvious link with Buchenwald was easily made. Here after all the saying adorned the entrance gate. The barbed wire and the smokestacks with decorative clouds in between were associated with destruction camps. An allusion to Buchenwald was not really intended stated Studio Job on tv. A question about a possible reference to Buchenwald foiled Smeets with “Wahhh, I would not like to phrase it as such". The words 'To each his own' is in fact a very light utterance, said Nynagel and Smeets added that the arch with bell was more a reference to a gate in the movie Once Upon A Time In The West. It stayed unclear why the duo whished to weaken the obvious link with Buchenwald and the destruction camps. Even after showing a table-cover provided with an abstract design of Auschwitz-Birkenau a direct explanation lacked. The deduced image was designed as a tablecloth for the VIP lounge, a dynamic space that the duo plotted for the Groninger Museum. A commentary of Job Smeets on Internet announced that the fence was meant as a reference to “Guantanamo Bay, the Jap camps, the camps in Bosnia and Second World war, of course.” The table-cover with Auschwitz design was a response to the art piece Hell of Jake and Dinos Chapman that was shown in the Groninger Museum in 2002-2003. It is a fact that Studio Job always seeks for icons and therefore they also for a fence icon with a not uninteresting question "what is a fence and why do we need a fence as human beings?" In this way they came up with the above described artwork. The aim of this Holocaust art was to evoke a discussion about the position of design toward art. Which discussion stayed unclear though, also on the day after during a second broadcast. A media revolt was born. Experts dominated the conversation and cried shame upon this, neighbours and the CIDI (Center for Information and Documentation Israel demanded a building freeze, because the design gave offence to the victims and had no respect for them. The building construction of the fence was finally not proceeded when journalist Arnold Karskens discovered in the Centraal Archief Bijzondere Rechtspleging (Central Archive Special Jurisdiction) that Jacobus Hendrikus Bakker, grandfather of Jack Bakker - the collector and commissioner of the fence - had been a member of the NSB and had worked between 1940 - 1945 for the German Luftwaffe and the Todt, a German organisation of governmental building sites. After the war J.B. Bakker was imprisoned for one and a half year because of collaboration. For Jack Bakker this unveiling about his grandfather was the traw that broke the camel's back. "Much to my regret I find that it is linked with matters that I have not wished when I commissioned the gateway, says Bakker.’ Meanwhile the Buchenwald fence was called Nazi fence and with this it perished ingloriously. Perhaps quite a shame, because the questions about what a fence means and why we need such a system were in this way not brought into the picture. What did Studio Job do wrong? Art on Holocaust, or Holocaust art has become in the meantime a genre in itself within which shocking art works are not kept out of the way. The British duo Jake and Dinos Chapman showed Hell in the Groninger Museum in 2002-2003. An art piece consisting of several show cases in which the German concentration camp was simulated with equipment as used in model building. A few years earlier a Polish artist, Zbigniew Libera, put LEGO Concentrationcamp Set (1996) ‘on the market'. i.e. a set of Lego boxes one may build a concentration camp with. I don't know if this included a gas chamber. To stick to fashion and design of Studio Job, in 1998 American Tom Sachs designed Prada Deathcamp, a model of a camp constructed of the packaging of the Italian fashion brand. These art works too caused an inevitable agitation. Nevertheless they were put on display and even purchased by museums. The crux of Studio Job's problem was that a proper story did not come off. Like art critic Rutger Pontzen wrote: “In spite of the fingerspitzengefühl that Smeets and Tynagel have for ‘our time’, one can not catch the design duo being engaged in the slightest sense. Their hedonistic approach turns everything they get in their hands into a bling-bling world: cupboards, globes, teacups, leaded glass windows. In order to make things a bit more challenging now also a concentration camp is introduced. The holocaust as design, it could be the next step to accepting the war, of course. But that is the point: who is it who wishes that the persecution of the Jews becomes a sanctioned lifestyle thing”. It was a pity that with respect to content a firm discussion on the designs of Studio Job failed to appear. It certainly made a point on what the table-cover well represented, in whatever way here out of place perhaps, namely the fact that Auschwitz had become an icon. What exactly that icon impersonated or how, why and of which Auschwitz had become an icon was not made clear at all, unfortunately. As also stayed unclear what the meaning of that Buchenwald fence is, apart from being an icon of a fence as phenomenon. What precisely is at stake when you parrot a camp or in this case a part of it? With these questions the Lego gas chamber popped up in my mind again. When my son built his gas chamber the goal was to transform mankind into the good, and for his part a certain degree of engagement cannot be denied. Libera as well had his own intentions with his LEGO Concentrationcamp Set and these, simply said, have to be looked for in a critical urge to analyse traditional dogmas towards the commemoration of the holocaust, education and the position of contemporary art. Again, what was Studio Job striving for with the Buchenwald fence or maybe more interesting to question, what activated the collector to provide the entrance of his mansion with a gate-way that prompts for an association with destruction camps? Building a camp yourself. Artist Joep van Lieshout did it once before already. He did not built this for a critical analysis on the commemoration of the holocaust and education through the arts, but for creating a society, called Slave City, that delivers a maximum profit on behalf of high prosperity. All products are recycled, even in the case when slaves don't function anymore. His use of slaves reminds one Animal Farm of George Orwell. The horse named Cleaver being deathly sick is not taken to the hospital, but sold to skinner Adolf Slime pot, Horse butcher and Glue boiler; merchant in Hides and Bone meal, Supplier to Dog kennels. Out of the profit jenever was bought. Slave City is a model for an utopian society in which everything is very rationally controlled, i.e. for officials and politicians utopia, for inhabitants an anti-utopia. Similar to the way the German concentration camps had been intentionally organised and where its structure had to shape the ideal city and society in general. The architecture was created for the use of surveillance and discipline of the inhabitants and of destruction, if necessary. This well-thought-out camp society in which everything runs like a precise clockwork inspired Frank Zappa to make his film 200 Motels. He invited the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra to perform in a copied concentration camp. The camp served as symbol for everything that abridged the individual freedom and particularly creative freedom. The concentration camp in the movie 200 Motels is Zappa's eyes a concentration camp of entertainment, a music camp sponsored by the United States Government. Above the entrance of the camp in 200 Motels the words ‘Work liberates us all’ could be read, a cynical allusion to the Nazi camps with its ‘Arbeit macht frei’ gateway. In reference to the concentration camps Zappa pronounced his strong feelings about the life of musicians. The music industry is corrupt and is subject to the capitalistic system that encapsulates creativity in favour of the business. Zappa wanted to show us that life in apparently a free city differs very little from the organisation mould in a concentration camp and that power relations within these systems may also be found in the so-called free existence of musicians, in playing in a band and life on the Road. The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra performing their music in a parroted concentration camp was a metaphor of the musician's life. “One may state that Slave City in various ways displays resemblances with our society, but I would never say: 'this is good or this is bad'. That is what the spectator has to find out" according to Joep van Lieshout. The camps of Van Lieshout and Zappa are indirectly referring to forms of organisation and systems in our daily life. Once again a recollection came up in my mind. The rituals I experienced in the music festival Lowlands reminded me of the ones in a camp like I have read in diaries of survivors. At the gateway my name on the ticket was transformed into a barcode, my wrist was provided with a bracelet, personal properties like drugs and booze had to be dumped into waste containers: eating and drinking was only allowed as long as products were sold by the organisation. For purchases the organisation had circulated own "camp money". Sleeping occurred on packed camping sites that were continuously guarded by bright floodlights overnight and teams of attendants with dogs. Admission, food, drinks, use of sanitary fittings, tent with music, for everything one had to queue up and wait for a long time. Without any explanation one could be bluntly stopped and searched. The idea that one was allowed, or/and had to be at ease within the fences of the festival was a paradox. In other words everyone was a mortified universal festival-goer who adapted to the laws of the organizer. The organisation structure of this festival was not very much inferior to what we know of a total-architecture: qualified by a barrier of closed doors, high walls, barbed wire or environmental separations like cliff ridges, water, woods or heathland. All components of life like sleeping, work, entertainment are performed on one and the same spot and authority. These activities are grouped in a tight scheme. A basic drive is to enforce the inhabitants to transform which already begins at the arrival: the mortification as self-inflicted privation of the ego. The inhabitant has to deposit his personal belongings, his hair is shaven, he gets a uniform and his name is altered into a number. It is a ritual that we observe in barracks, prisons, monasteries, boarding schools and concentration camps. I have never revisited that festival and most probably I will never do. Especially after I read that experiments had started to provide bracelets with a Global Positioning System (GPS). Each visitor may be observed and undesirable behaviour can be detected and banned. Suddenly Woodstock and Kralingen are faraway. Dutch politician Fleur Agema of the PVV (Party For Freedom) designed an ideal prison, being a student at the Hogeschool van de Kunsten in Utrecht in 2004. Artist Jonas Staal had rendered her design into a scale model based on her master thesis of 344 pages. The prison consists of a heavily built edifice that is comprehensive, dark and sinister. The building is constructed of black and grey concrete and surrounded by towering fences. The cells are caverns with a heightened bed of concrete and a lump with a hole as toilet of the same material. A split in the wall serves as window. It causes a ray of light. The prison has also a section in which the prisoners are prepared to return to the community. These sections have names like: "The Fortress", "The Encampment", "Artillery House" and also "The District". The latter is a national New Housing Estate (in Dutch Vinex/Vierde Nota Ruimtelijke Ordening Extra) area with surveillance cameras. Jonas Staal came to the conclusion that Agema's architecture seamless fitted perfectly in the social order of the ideals of the PVV: '[…] the striving for a society with discipline, efficiency and productivity in which all "non productive elements" are cleansed." Staal says: "In this case it is about prisoners, but in the ideology of the PVV these could easily as well have been Muslims, unemployed people or artists. Everyone who does not fit into the concept of productivity is banned." This reminds one of Slave City of Van Lieshout. In order to superintend and regulate somebody one does not need a stone, iron or wood anymore today. Digitilisation is marching on. In this way for example punishment sentences with electronic detention will be served outside of the penitentiary institutions. Walls, barbwire fencing, watchtowers, canals, access gateways - all these known icons of total-architecture can be found in a concentration camp and replaced by electronic systems. One could speak of digital walls composed of a network of surveillance cameras, digital passes, iris scanners and face recognition systems. Not only systems give access to a specific territory, but also habitat areas have to protect against evil-minded intruders. London and Amsterdam too have a ring of steel at their disposal (comparable to the old castle-moat) that have to safeguard the city with hundred thousands of surveillance cameras. These systems are becoming more and more advanced. For example a scientific research team experiments with monitoring systems that recognize unusual behaviour. With this an intelligent surveillance camera could protect privacy much better. A computer recognizes human torsos, arms and legs in such a way that defining the intentions of individuals becomes easier. Also inspection of authorities through digital social networks is merely a matter of time. We all know about this evolvement, but for the benefit of security we don't take offence at this or we are still indifferent. It is like a theory on medieval villages that were invented to monitor the farmers for control and for enforcement of hard labour. The castle was not so much there for protection, but more for a substitute of watchtowers similar to the concentration camps. When is the moment that our cities have become such camps with cameras as digital watchtowers? What would have happened in case Studio Job would have designed an entrance gate that referred less explicit to Buchenwald and Auschwitz. These names and sites are connected to traumatic experiences and painful recollections. No wonder the subject was encountered as shocking. The wound Auschwitz is not healed at all yet. Worse than that, the persecution of Jews has become a moral point of calibration in history that is rediscovered again and again and stays up-to-date, with or without incidents like the Buchenwald fence. Just imagine that the duo would have designed a gateway that would have revealed the question of what makes a fence and why do we need fences anyway? So a gateway that brings up the topic of the system and camp structure. And if they would have placed this gateway - or gateways - above the access roads to Amsterdam with the aim to draw attention to our approaching of a social environment with supervision. An environment that is created for our freedom and safety but yet at the same time - while thinking of the medieval village and the concept of Fleur Agema - may be used for the opposite to have discipline to become efficient peasants and citizens. In short an entrance gate that could have provoked a discussion of the consequences of creating social environments with digitalized attendance. And what would have happened if the Buchenwald fence, encircling the country estate of the collector, in fact had been built? A bell would have been hung without any offensive slogan and the gateway together with the fence would have been as grim as the camps as we know them, what would he have had built and with what intentions? Would he have built his own camp? Would he have become an admirer and collector of the Nazi-heritage, regardless to how fake the gateway might have been? Or would he have hold up a mirror to us to show in what way ideal communities nowadays are being planned and built? If one would like to see that, he should take a walk through a prosperous suburb. The villas are surrounded by high walls or fences provided by innumerable cameras. In the series Nederland van boven a new trend was shown. Districts were protected by a canal and closed of by gates that wouldn’t be inferior to old castle- or town gates, also known as gated communities. But still. In my opinion the collector meant no harm when he approached Studio Job to design a fence. But what he actually tried to express with the fence remained unclear. His argumentation for bringing the project to an end stays cryptic, ‘Much to my regret I find that it is linked with matters that I have not wished when I commissioned the gateway.’ But what did he wish for? Of course a fence surrounding his property. And his property is besides an estate also an art collection. He wanted to safeguard his collection and as many museums do, to create a system in order to save the art for posterity. Apparently the society works like that, that a sort of concentration camp has to be build to secure our art (of course that is what Studio Job was trying to show us). Which museum nowadays isn’t supplied with security gates, surveillance cameras and guards that if necessary follow the visitor closely until he is outside again. The museum as a camp, Van Lieshout could have invented it, but a camp for the elevation of the citizen, because for that museums were once founded. The collector would have built a good camp, if the Buchenwald fence had been realized. Visitors would admire his art by the time his villa would have become a museum, as this occurs nowadays. They would have wandered and left his property enlightened. That was not to be. In fact the collector was turned into a malicious camp commander even before the construction. Roel Hijink, Amsterdam 2013 For this article I have used the following sources: Lars Anderson, ‘We kregen de afluisterstaat die we wilden’, in: de Volkskrant dinsdag 11 juni 2013. Arie Elshout, ‘VS zien van de hele wereld mailverkeer’, in: de Volkskrant zaterdag 8 juni 2013. Hans den Hartog Jager, ‘Gefascineerd door macht’, interview met Joep van Lieshout, in: Oog Magazine, november 2008. Marc Hijink, ‘Intelligente oren en ogen, in: NRC Handelsblad zaterdag 8 januari en zondag 9 januari 2011. Arnold Karskens, ‘Bizarre soap rond Buchenwaldhek’, in: Dagblad De Pers, donderdag 2 februari 2012. Arnold Karskens, ‘Nazi-hek definitief van de baan’, in: Dagblad De Pers, vrijdag 3 februari 2012. Jannetje Koelewijn, ‘De buren blijven boos om het hek’, in: NRC Handelsblad, vrijdag 30 december 2011. Victor de Kok, ‘Bouw “Buchenwald”-hek gaat toch door in Bentveld’, in: de Volkskrant zaterdag 24 december 2011. Victor de Kok, ‘Bouw “Buchenwaldhek” vooralsnog van de baan’, in: de Volkskrant, vrijdag 30 december 2011. Norman L. Kleeblatt (edited), Mirroring Evil. Nazi Imagery/Recent Art, 2001 The Jewish Museum, New York. Victor de Kok, ‘Blauwdruk. Mee met beeldend kunstenaar Jonas Staal’, in: de Volkskrant, donderdag 17 november 2011. Hugo Logten, ‘Digitale ring scant alle auto’s’, Het Parool woensdag 7 september 2011. Evgeny Morozov, ‘Internetsurveillance’, in: NRC Handelsblad zaterdag 15 januari en zondag 16 januari 2011. Rutger Pontzen, ‘Holocaust als design’, in: de Volkskrant, vrijdag 6 januari 2012. Politiek Kunstbezit III: Gesloten Architectuur. Een project van Jonas Staal naar een concept van Fleur Agema, Onomatopee, 2011. Toelichting Job Smeets, december 2011, Antwerpen: http://historiek-net/blogs/de-holocaust-gewoon-een-thematiek-5559. Gelezen 2 februari 2012. Jan Willem Stenvers, ‘Overal drones: schrikbeeld of ideaal?, in: Trouw zaterdag 11 mei 2013. Roel Hijink studied at the Academy of Visual Arts Maastricht and Art History at the University of Amsterdam. In 2010 he obtained his doctorate on the dissertation ‘Former concentration camps. The monumentalizing of the German camps in the Netherlands’, which was published in book form by Uitgeverij Verloren in 2012. Currently he is working on the book ‘ 1942. Auschwitz vs Victory Boogie Woogie’, which describes how the two icons of the twentieth century come together in one single painting.

|